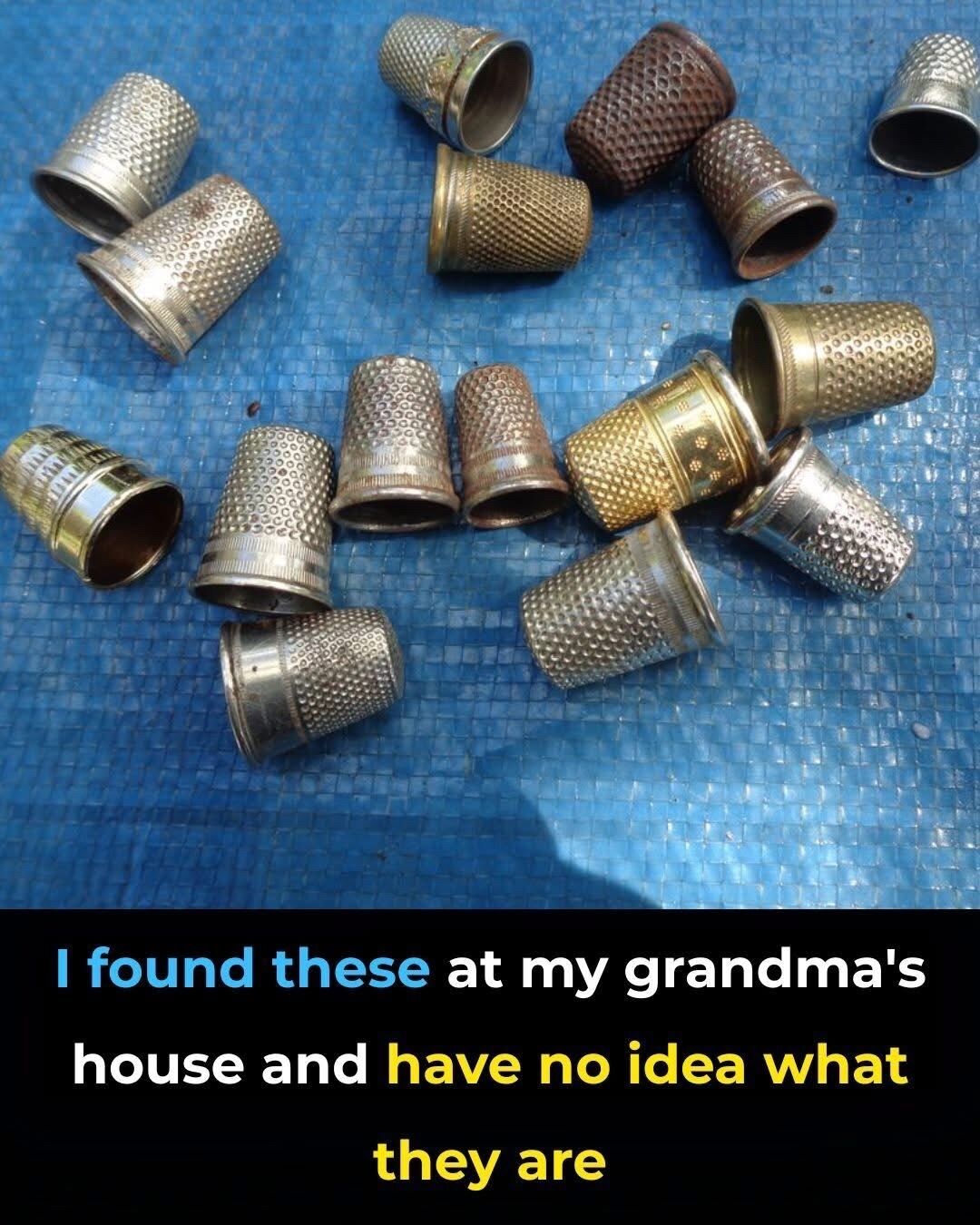

Thimbles are small, unassuming objects, yet their role in the history of sewing and textile work is far larger than their size suggests. At their core, thimbles are protective tools designed to shield the fingers from repeated needle pricks while allowing the sewer to apply steady pressure when guiding a needle through fabric. Worn most commonly on the middle finger or thumb, a thimble acts as a firm barrier between skin and metal, transforming what could be a painful or tiring task into one that is efficient and controlled. This simple function has made thimbles indispensable to generations of tailors, seamstresses, quilters, and artisans. Beyond basic protection, thimbles enhance dexterity and confidence, particularly when working with thick, layered, or resistant materials such as denim, canvas, wool, or leather. The ability to push a needle without fear of injury allows for smoother stitches and better overall craftsmanship. Over time, thimbles evolved from purely functional tools into objects of personal preference and even artistic expression, appearing in a wide range of sizes, shapes, textures, and decorative finishes. While modern sewing machines dominate many aspects of textile production today, the thimble remains a symbol of handcraft, patience, and the enduring value of skilled manual work.

The history of the thimble stretches back thousands of years, underscoring its importance in daily life long before industrialization. Archaeological evidence shows that early forms of thimbles were used in ancient China and throughout the Roman Empire, crafted from materials such as bone, bronze, leather, and ivory. These early examples reveal not only the practicality of the tool but also the ingenuity of early societies in adapting materials to meet everyday needs. In medieval Europe, thimbles became more standardized in shape and were commonly made from brass or bronze, often featuring small indentations to grip the needle. By the 16th and 17th centuries, thimbles had taken on additional cultural and symbolic value. Wealthier individuals commissioned thimbles made from silver or gold, sometimes decorated with engraved patterns, religious symbols, or gemstones. These ornate thimbles were not merely sewing aids; they were expressions of status and refinement. In some cultures, thimbles were given as tokens of affection, engagement gifts, or keepsakes passed down through generations. Their presence in dowries and family heirlooms highlights how closely sewing tools were tied to domestic life, skill, and identity, particularly for women whose craftsmanship was central to household survival and social standing.

Functionally, the thimble serves several interconnected purposes that go far beyond preventing discomfort. One of its primary uses is enabling the sewer to push a needle cleanly and consistently through fabric. Without a thimble, repeated pressure on the fingertip can lead to soreness, calluses, or injury, especially during prolonged sewing sessions. A thimble distributes force evenly, allowing greater strength and precision with less effort. This is especially important when sewing dense materials or navigating multiple layers, such as in quilting or upholstery work. Thimbles also contribute to improved accuracy and control, helping maintain straight seams and even stitch lengths. For professionals and serious hobbyists alike, this control translates into higher-quality results and faster workflow. Specialized sewing disciplines rely heavily on the right type of thimble: embroiderers benefit from lightweight designs that preserve fine motor control, while leatherworkers require sturdy metal thimbles capable of withstanding significant force. In every case, the thimble becomes an extension of the hand, subtly guiding the needle and enhancing the sewer’s connection to the material.

see next page

ADVERTISEMENT